The Enduring Legacy: How the Great Victory 80 Years Ago Shapes Today’s China

To truly grasp the significance of the Great Victory, we must look beyond the awe-inspiring display of military might, back to the historic background that still echos till today.

By Ryan Yeh

September 3, 2025, marks the 80th anniversary of China’s victory in the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. On that day, as the world’s gaze once again turns to Beijing Tian’anmen Square, it will witness a grand, meticulously organized military parade. Neatly aligned formations, advanced weaponry, and resounding slogans—all will showcase to the world a modern China that is strong, confident, and disciplined. Yet to truly grasp the significance of this grand event, we must look beyond the awe-inspiring display of military might, back to the end of that brutal war 80 years ago, and listen to the echo that still resonates deep within the soul of the Chinese nation.

To the Western world, China’s victory in the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression may seem like a distant and vague chapter of the broader canvas of World War II—an “Eastern battlefield.” But for the Chinese people, it is an epic steeped in blood and tears, the starting point of the modern narrative of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. It was not only a military triumph, but also a spiritual rebirth—one that profoundly shaped China’s national identity, collective character, and the very foundation of its worldview today. Without understanding this chapter of history, one cannot truly comprehend China’s ambitions, dreams, or the perseverance and resolve that, at times, puzzle or even unsettle the world.

The Forgotten Ally and the End of a Century of Humiliation

In Western historical memory, World War II began in 1939 with Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland. But for China, this existential war had already erupted in full force on July 7, 1937, with the gunfire at the Lugou Bridge—and some would trace its origin even earlier, to Japan’s invasion of Northeast China in 1931. As Oxford historian Rana Mitter pointed out in his book Forgotten Ally, China was the first nation to engage in a prolonged and large-scale war against the Axis powers, yet in the global narrative that followed the war, China’s striving was disproportionately forgotten.

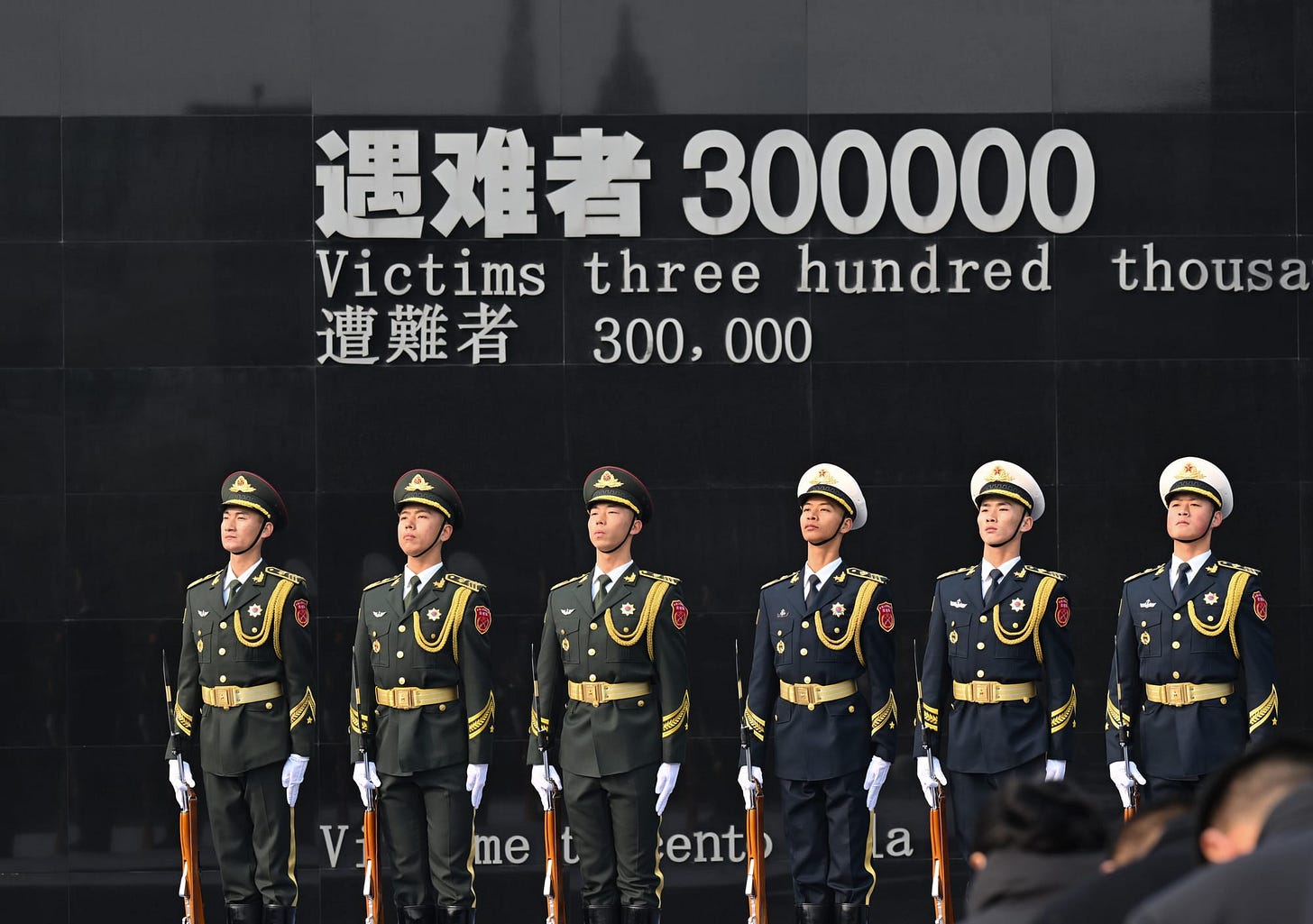

This war was far more brutal than most people could have realize. It was not merely a conflict between armies, but a total war waged against the entire Chinese nation and its civilization. More than 35 million Chinese soldiers and civilians were killed or wounded—a number that exceeded the total casualties of all other Allied nations combined. The Nanjing Massacre alone, in which hundreds of thousands of civilians were brutally slaughtered over the course of just a few weeks, was a stark example of the countless atrocities committed. Over the course of eight years of total resistance, most of China’s territory was ravaged by war, and hundreds of millions were displaced from their homes.

To fully understand what this war meant to the Chinese people, it must be seen within a broader historical context—namely, the “Century of National Humiliation” that began with the First Opium War in 1840. For nearly a hundred years, China, once proud of its status as the “Celestial Empire,” was forced to sign a series of unequal treaties under the military pressure of Western powers and Japan. The nation lost territory, paid massive indemnities, and saw its sovereignty steadily eroded. It came to be mocked as the “Sick Man of East Asia,” while its people were dismissed as a disunited and powerless mass. This collective trauma—of falling from the heights of civilization into humiliation and subjugation—left the deepest scars on generations of Chinese.

Thus, the victory in 1945 meant far more than the end of a war. It marked the moment when the Chinese nation, through immense sacrifice, finally brought an end to a century of humiliation. For the first time, the Chinese people came to believe that they could defeat seemingly invincible enemies through their own strength—that they could once again take control of their own future. It was a profound psychological turning point: China rose from a semi-colonial state subjected to repeated aggression, to a sovereign nation standing on its own feet.

The Birth of Modern Chinese National Identity

Sun Yat-sen once lamented that modern China was “a sheet of loose sand.” Before the war, the country was plagued by warlordism and rampant regionalism, and for many Chinese people, the very concept of a unified nation remained vague. But Japan’s full-scale invasion acted like a searing brand—it forced those scattered grains to fuse together, forging a sense of national unity in the face of destruction.

The war gave rise to an unprecedented nationwide mobilization. “Regardless of region, regardless of age—everyone has a duty to defend the land against invasion”: this call to arms echoed across the country. The once-feuding Nationalists and Communists set aside their differences and formed the United Front against Japanese Aggression to confront a common enemy. Though tensions and mistrust ran deep, the ancient belief that “brothers may quarrel within the family, but must unite against external threats” prevailed over ideological divisions in the face of national peril.

One of the most symbolic events was the westward migration of scholars and universities. In order to carry forward the legacy of Chinese civilization, faculty and students from Peking University, Tsinghua University, and Nankai University trekked thousands of kilometers across half the country. They eventually regrouped in Kunming, a city in China’s southwest, to form the National South-West Associated University. Carrying heavy books and laboratory equipment on their backs, they continued teaching and research under thatched roofs and by the light of oil lamps, keeping the cultural lineage of China alive. This tragic yet heroic cultural “Long March” was, in itself, a powerful declaration of national identity: no matter how shattered the land, as long as its culture and spirit endure, the nation will not perish.

Likewise, countless factories were dismantled along the coast and relocated to the vast interior rear areas—carried piece by piece by workers, on their backs and shoulders. In Chongqing, people endured five years of relentless, indiscriminate bombing by the Japanese air force. They took shelter in makeshift air raid tunnels and, in the lulls between explosions, rebuilt their homes and kept the wartime economy running.

In this historical process, the Communist Party of China (CPC) played the role of a mainstay. The Eighth Route Army and the New Fourth Army, led by the Party, penetrated deep behind enemy lines, extensively mobilized the masses, waged guerrilla warfare, and established vast anti-Japanese base areas. Mao Zedong’s 1938 work On Protracted War provided crucial strategic guidance throughout the war. Through land policies such as rent and interest reduction and deeply rooted political and ideological work, CPC effectively organized and mobilized millions of peasants, turning them not only into fighters against aggression but also into the main force of national liberation and the rebirth of the country. This cascade ocean wave of nationwide resistance greatly depleted the Japanese army and dragged it into the quagmire of a national war. It was the Communist Party’s strong organizational and mobilization capacity that demonstrated the Chinese people’s determination to resist foreign aggression and defend national sovereignty, becoming the key to victory in the war.

Through shared suffering, resistance, and sacrifice, the identity of being “Chinese” began to transcend region, class, and political affiliation—it became something real and deeply felt. The concept of the “Chinese nation,” once confined to intellectual discourse, was forged into reality through the blood, lives, and emotions of hundreds of millions, in the crucible of war.

Perseverance, Devotion, and Love for the Nation

If national identity was shaped by the war on a broad scale, then the forging of national character could be seen in the quiet strength and integrity of countless individuals. This war etched three defining qualities deep into the collective personality of the Chinese people.

First and foremost was perseverance. Over the course of eight grueling years, the Chinese people resisted an enemy whose industrial might far surpassed their own—often with little more than flesh and blood against steel. In the Battle of Shanghai, Chinese forces suffered staggering casualties as they held the city for three months, shattering Japan’s arrogant claim that China could be conquered in three. This strategy of “trading space for time”, the refusal to surrender even in its darkest hour—reflected the will of an ancient nation to survive against all odds. That same spirit of endurance lives on today, embodied in the Chinese people’s quiet belief that whatever the hardship, they can hold on, press through, and outlast it.

Second came the spirit of sacrificing life for the survival of the nation. The young generations at that time should have been students in classrooms, workers in factories, or farmers in the fields—yet they marched unflinchingly to the battlefield instead. Among them, Air Force pilots faced the most perilous odds—their average life expectancy, once they began flying, was just a few months. Before takeoff, many would write farewell letters: “If we do not return, please remember—we are trading our lives for even one more day of our country.” This readiness to face death, this unwavering resolve to trade individual life for the survival of the collective, became a profoundly moving moral ideal—one etched into the soul of the nation.

Another defining trait is a deep, almost instinctive love for both one’s family and the nation. This sentiment—often encapsulated in the Chinese concept of jia guo qing huai(家国情怀)—has no direct equivalent in Western discourse. It is more than just patriotism. In Chinese culture, “home” (jia) and “nation” (guo) are seen as deeply interconnected. There can be no home without a nation; if the nation falls, so does the family. During the war, this belief became a lived reality for millions. The scattering of families, the loss of loved ones—all were intimately tied to the fate of the country. To defend the nation was to defend one’s own home. This deeply rooted emotional bond explains why the Chinese people maintain such a profound attachment to national unity and strength. For many, it is not an abstract idea but the foundation of personal security and belonging.

Sovereignty, Peace, and Power: A Delicate Balance

The victory in the war, along with a century of preceding humiliation, fundamentally reshaped China’s worldview and continues to shape its foreign policy and national strategy to this day.

First, sovereignty is sacred. For a nation that has experienced the loss of territory and the trampling of its sovereignty, “sovereignty and territorial integrity” is far more than a diplomatic phrase — it is a red line drawn in blood. This is why China adopts an uncompromising stance on issues like Taiwan and the South China Sea. To many in the West, such positions may be misinterpreted as expressions of aggressive nationalism. But in the Chinese psyche, they represent a deeply rooted instinct to prevent the recurrence of historical trauma.

Second, peace without strength is fragile. The Chinese people’s yearning for peace is genuine—few nations understand the brutality of war more deeply than China. But history has offered another painful lesson: “A weak nation will be bullied.” A fractured and powerless country cannot safeguard peace; it can only be carved up by others. In China’s worldview, peace and strength are not opposites but two sides of the same coin. Building a strong economy and a modern military is not about aggression or expansion. It is about ensuring that the humiliations are never repeated. It is about having the confidence and capability to defend peace. With this perspective, one can better understand the logic behind China’s display of strength in military parades: “Only those who are prepared for war can truly prevent it.” It is a defensive posture, born of a deep-seated sense of insecurity.

Third, the pursuit of equal status and international respect. The victory in the war allowed China to abolish most of the unequal treaties and become a founding member of the United Nations as well as one of the five permanent members of the Security Council. This legally marked China’s return to the ranks of major world powers. Since then, China has sought equal respect and a voice on the international stage. What China pursues in its diplomacy today is precisely to wash away the humiliating image of being at the mercy of others, and to participate in global governance as an equal and confident partner.

Echoes of History, Stance of Today

When we turn our gaze back to the grand commemorations of the 80th anniversary, what we may witness now is perhaps no longer just a military parade showcasing might.

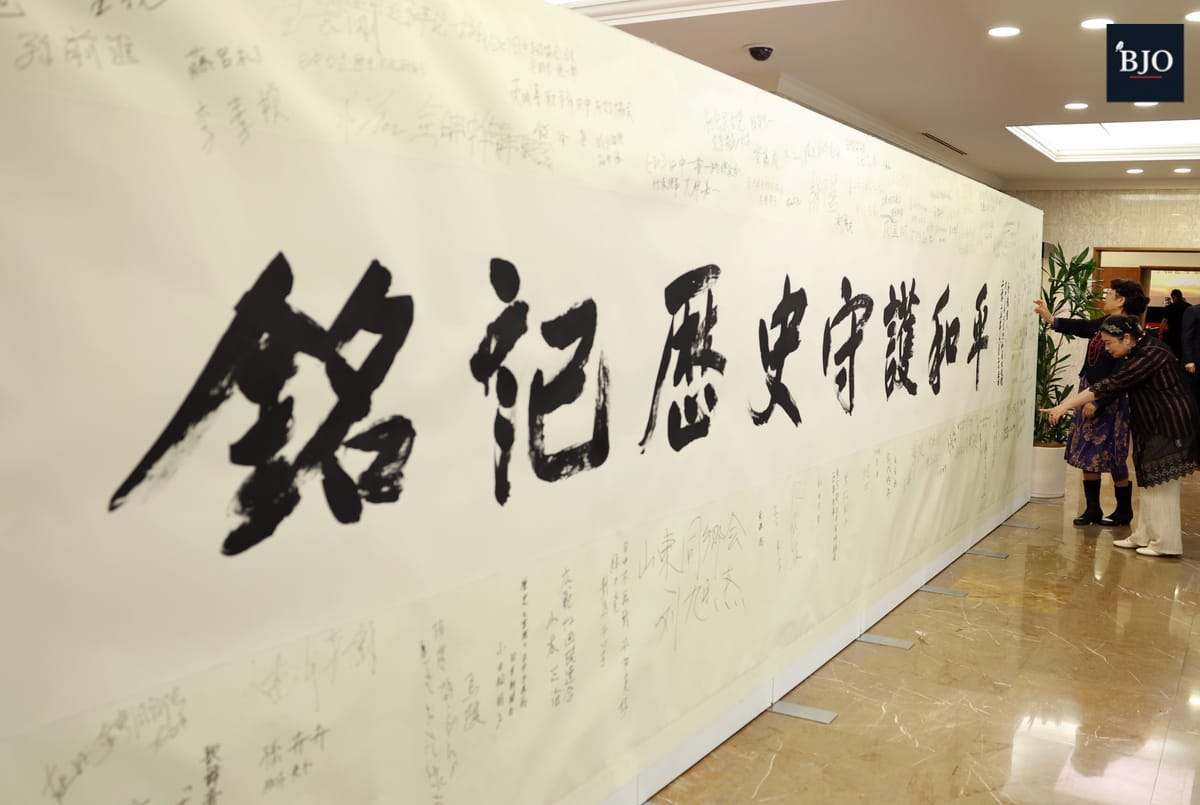

The synchronized footsteps echo the ten-thousand-mile Long March once trodden in straw sandals; the advanced fighter jets carry the legacy of ancestors who soared toward enemy ships in rudimentary planes; the nation’s formidable stature today honors the tens of millions perished in suffering. This commemoration is, first and foremost, for the Chinese people themselves. It is a collective national rite of remembrance, a solemn lesson where one generation tells the next, ‘This is where we came from.’ It is a vow to those forebears who gave everything for the survival of the nation: Your sacrifice is not forgotten. The strong China you dreamed of—free from humiliation—is now a reality.

To the world, listening to these echoes of history provides a key to understanding China today. When you witness China's steadfast commitment to sovereignty, recall the scars of its 'Century of Humiliation.' When you observe China's vigorous defense modernization, please understand a nation's visceral fear that 'A weak nation will be bullied backwardness invites aggression.' And when you see the Chinese people's extraordinary drive for national rejuvenation, recognize their profound yearning for lasting peace and stability.

China's commitment to peace is no diplomatic expediency, but springs from the profound collective memory of a nation reborn from the ashes of its modern history - a people's deepest reflection on suffering forged through experience. This is a sacred vow for peace, made by those who have witnessed hell itself. When the world understands this weighty historical legacy, it may forge deeper empathy with China, joining hands to safeguard our era's hard-won peace.

Ryan Yeh is a Beijing-based observer of international affairs. The views don't necessarily reflect those of BeijingOpinion.